- Advertisements. I understand your need to get the money in, but do it with decency. Don't clutter my screen with flashing and blinking crap, don't have ads appear over an article I'm just trying to read and don't mess up the formatting so much I can't figure out where the text continues. Also, if it is an advertisement, call it an advertisement. Don't call it a "welcome screen" or a "hello from our sponsor," who are you trying to fool? I have to disappoint you though, the only instances I click on ads are accidentally. If I want product information, I know how to get it, and it's not on your website. As far as I am concerned product placement on websites is entirely useless.

Example: Forbes. Try reading a single article without going insane. - Emails. Never ever send me emails I didn't ask for. And no, I am not interested in your news, your updates, or your great community events. It is totally sufficient if I learn of that next time I log in. If there is such a time. The services I am most pleased with are Google, Twitter and Facebook. I never received a single email from them that I didn't ask for. Make "no emails" the default and don't cheat by requiring me to uncheck a dozen different boxes.

Example: Bank of America. Even though I complained several times already when I was a customer, they still send me advertisments after I finally managed to close all my accounts. Same with United Airlines, SiteMeter, Neon, and a dozen other websites that require subscription and then clog your inbox with html emails. - Over-the-top Security. Unless you are indeed storing sensitive information, don't ask for 8 digit passwords containing numbers, letters and special symbols. Don't suspend accounts if users guess a wrong password three times if the only thing you're protecting is their nickname. Don't ask for information that's none of your business to begin with. Btw, I don't actually live in Algeria and my birth year isn't 1962 either. Also, have an option for password recovery that doesn't require the registered email address. I have a couple of dead accounts because the email address I used to register is no longer active and I can't recall the password. Yet, the reminder is sent to that address.

- Can't delete my account: Have an option to delete an account. It might hurt, but there are people who figure out they don't want your service after all. If you don't have this option users who want to leave will just scramble up their profile information and log out a last time, leaving you with a dead account. At the very least, clean up your inactive accounts every now and then.

- Clutter overdose. Don't clutter your website with a thousand flash animations, widgets, java-scripts and other stuff. Keep it simple. Why do you have the weather forecast on your site? If that's what I'd be looking for, I'd be looking elsewhere. Also, it is self-evident but can't be repeated sufficiently often: please use a clear and intuitive layout that is the same for all sites showing the location in the menu tree. And please do mark visited links in a different color. To achieve that purpose, don't hesitate to copy templates from highly frequented websites and modify them slighthy to meet your needs. That's how natural selection works.

- Sound effects. The surest and fastest way to get me off your site is background music, ads with sound effects, or speaking avatars. Especially bad if the sound can't be turned off. Look, I might not be alone, I really don't want my computer to make embarrassing noises, okay?

- Browser incompatibility. You'd think that's the first thing everybody learns who designs websites: different browsers will interpret your template differently. Have a look at it at least with MS Internet Explorer, Safari, Firefox and Google Chrome. Or have somebody else look at it who uses these browsers and send you a screenshot. You'll be shocked how crappy your website suddenly looks.

Example: The ESTA website that couldn't be opened with Google Chrome (they meanwhile fixed the problem). - Local lingo. If you're hosting a forum, don't invent your own html encoding. Just let users enter html tags and screen for unwanted tags. How I am supposed to recall if you want [ .\] for a link or ".":., or *.* is italics or maybe boldface? Example: NatureNetworks. Can never recall how to enter a link. Also, don't give fancy names to menu items that nobody knows what they mean. What is "avant garde" or "horizons" supposed to be?

- Who the fuck are you and what do you want? Don't force me to go to Whois to look up who you are. Have an "about" and a valid contact address. I want to know who you are, what your background and your motivation is. Everything else smells fishy unless you have a good reason to maintain anonymity - and if you have that reason I want to know it as well. Also, tell me upfront what you do. For example, if your "international" company doesn't ship anywhere but in the USA, tell me before I've spent half an hour putting items in your cart.

- Your scripts suck! Prepare for failure: If you have any forms on your site, always, always, always, provide a message confirming the script was executed properly. The message should contain all the submitted information together with an option for correction in case there's a problem. Further, keep in mind people's information might not fit into your great form for whatever reasons. Canadian Zipcodes do not consist of 5 digits. Some people really don't have a home phone. Worst thing ever: If your script returns an error and I'll have to fill out ALL fields again.

Monday, June 29, 2009

10 Reasons Why I Hate Your Website

Sunday, June 28, 2009

SuperPoke! Pets - An Emerging Market

Stefan and I have been following an interesting phenomenon: SuperPoke!Pets. SuperPoke, for those of you down on Earth, is a Facebook application you use to not only "poke" your friends, but to tickle, hug, wave at them. You can trow sheep at them, buy drinks for them, hate Monday with them, and so on. There is also a section for good causes, thus you can "fight global poverty with," "go green with," and "save water, shower with" etc.

Stefan and I have been following an interesting phenomenon: SuperPoke!Pets. SuperPoke, for those of you down on Earth, is a Facebook application you use to not only "poke" your friends, but to tickle, hug, wave at them. You can trow sheep at them, buy drinks for them, hate Monday with them, and so on. There is also a section for good causes, thus you can "fight global poverty with," "go green with," and "save water, shower with" etc.

These messages come with little pictures of pets, sheep, pigs, penguins, kittens. Everybody please: Oh, how cute. This application also exists for other social networking sites.

These messages come with little pictures of pets, sheep, pigs, penguins, kittens. Everybody please: Oh, how cute. This application also exists for other social networking sites.Since last year you can "adopt" a SuperPoke pet. It's somewhat like a Tamagotchi and it's for free. You get a website with a flash application showing your pet in some background, called a "habitat." You can feed, tickle, wash and play with your pet. If you don't do that regularly, it will look dirty, hungry and unhappy, the poor thing. If you play with your pet, you get "coins." You also get coins if you play with friend's pets or if these play with your pet.

With the coins you go to the "Pet Shop" and buy things to decorate your habitat with. That might be pictures of flowers, or clouds, or toys. You can also buy a new habitat, e.g. different rooms, a playground, a beach, a fitness room, and stuff for these.

Let me then introduce you to my pet, Fury, the sheep, on a picnic:

Cute, eh? Some of the gifs are animated, thus the butterflies are fluttering. Here is Fury's website (you'll have to get a pet yourself to play with it).

Cute, eh? Some of the gifs are animated, thus the butterflies are fluttering. Here is Fury's website (you'll have to get a pet yourself to play with it). There is also a member-forum where pet owners can ask questions like if their pet will die if they go on a trip and can't feed it (it won't), where you can suggest items for the Pet Shop, enter habitat contests, and so on. Further you can get all kinds of rewards for being a good pet owner and community member, there's "Pet Levels" and "Pet Fame" and all kinds of badges you can earn for being a good friend, having trendy accessories and so on. I haven't really figured it all out. After some weeks I started finding the flash animations somewhat annoying and repetitive.

Besides buying stuff with the coins you get from playing with the pets, you can buy "Gold" and go shopping in the "Gold Shop". The gold you buy 10:1 for US$ and charge it on your credit card. Needless to say, the "Gold Items" are fancier than the other ones. They are larger, they are animated, they are the Want-have-stuff. Every Monday, there's new items, and they are sold out really fast. That's right. I find this quite amazing. People buy little cartoon pictures of furniture to combine with a picture of a pet in a flash application. With real money.

The stuff doesn't look remotely realistic btw, the items are all 2-dimensional and you can't even scale them, meaning perspectives often don't fit together. Neither can you move your pet or get it to sit on a chair or play with a toy.

But here is the interesting part.

You can give "gifts" to other pet owners. Since many items in the Pet Shop are meanwhile sold out, it didn't take long for the forum to develop a trading post where people were arranging exchange of items, while others made "garage sales" on their habitats using the possibility to make mutual gifts. Since this was quite clumsy, you can now set up a "Have list" and a "Want list" on your profile. Together with the possibility to exchange messages this works quite well. Since one can't make a simultaneous exchange though there is some trust involved. For all I can tell though, cheating is virtually absent. If a trade has been successful, you can give a "reliable trader" compliment.

You can however only give items as gift, you can not transfer coins. So we have a barter economy! One that is cleanly separated from all other world markets. It is a quite centralized market though since pet owners can't produce any items themselves. Nevertheless, you'll notice some distinct features.

For example rare items are under high demand, because even if you don't want them, you can trade them on. (Since the community has been growing, older items are generally becoming rare.) Once items are sold out, their value becomes basically totally decoupled from the original price. One could argue they tend towards their "true value."

Other items are fairly frequently stocked up, like some food and furniture items. Their prices never change though. This strikes me as a great opportunity to find out how demand depends on the price and, if there was a way to provide supply, if prices reach equilibrium and under which circumstances. I also wonder whether the barter economy will eventually discover some suitable item that can take the place of money.

All together we seem to be witnessing the birth of a new market economy. It's itching in my fingers to see some data about consumer's behavior...

And finally, here is Stefan's pet: Struppi the puppy

Friday, June 26, 2009

Constraining Modified Dispersion Relations with Gamma Ray Bursts

Giovanni Amelino-Camelia and Lee Smolin have a new paper on the arXiv:

While the discussed effects on the propagation of photons are extremely tiny and way too feeble to be observable in experiments on Earth, they could add up when the travel is very long distance. In the models the authors consider, the strength of the effect depends on the energy of the photon. The speed of light is then no longer a constant but a function of the energy of the photon. In the low energy limit, photons travel with what we usually call THE speed of light, c [1].

To first approximation there are two cases: either the high energetic photons are faster than the low energetic ones, or the high energetic photons are slower than the low energetic ones. I would have guessed the majority of people had thought if such a scenario is true then the photons with higher energy should be faster. If only because we are secretly all dreaming of traveling faster than the speed of light. But that's not what the data seems to suggest to me.

These scenarios can be tested with signals from gamma ray bursts, highly energetic flashes of light originating in faraway Galaxies. Their spectrum covers a large range of energies. If one records photons of different energies with an exact timing, one can compare their arrival time. In my previous post we had been discussing the gamma ray burst GRB 080916C (the number encodes the date). In this burst, the high energy photons seem to be arriving with a delay relative to the lower energetic ones. However, the statistics of that one burst isn't very convincing. Yes, there was that one lazy high energy photon with 13 GeV that arrived 16.3 seconds after the onset of the burst. And okay, there were a couple more photons that seemed to be delayed, but then the low energy signal had two peaks rather than one. This might have indicated it was a fairly uncommon burst.

However, Giovanni and Lee sifted through some databases and found a couple more gamma ray bursts that were recorded during the last year that show similar characteristics, if not so pronounced. In all cases, the high energetic photons were delayed. Their paper offers a neat table summarizing these events, but unfortunately no statistical analysis for how significant the patterns are.

In the following sections of the paper they constrain several models with that data, most notably those who break and those who only deform Lorentz Invariance. In the first case, the universe has a preferred frame relative to which the energy of the photons is defined. In the second case there is no such preferred frame [2]. They further distinguish between the case where high energetic photons are faster (superluminal) and those in which they are slower (subluminal), and extract bounds on the quantum gravity scale for both cases. It is somewhat unintuitive to extract bounds also on the superluminal case when there is a trend in the data for higher energetic photons to arrive later, but it could be an astrophysical effect that is hiding superluminal propagation. The bounds on the superluminal case however are weaker.

There is quite a lot of astrophysics involved in the emission of these photons and the most conservative explanation for the delay is certainly that the photons were emitted with delay. While Giovianni and Lee's analysis offers useful first estimates, what would be needed is a procedure that allows to cleanly separate astrophysical source effects from effects during propagation. To do so, one had to extract the dependence of the signal on the distance to the source.

In the final section of the paper, Giovanni and Lee suggest to obtain further experimental data by looking for photons of even higher energies (that could be delayed up to months) or neutrinos that are emitted from the same source. In both cases, I wonder whether it is feasible to obtain any sensible statistic within the lifetime of the average physicist.

Altogether it is a very useful paper that summarizes the status. It leaves one wanting though for a more thorough data analysis.

[1] Not to be confused with theories with a varying speed of light which usually means a variation with time, not with energy.

[2] I wrote a paper showing the second case doesn't make sense if you have an energy dependent speed of ligh. You can wind yourself out of my proof by making your theory even weirder.

- Prospects for constraining quantum gravity dispersion with near term observations

arXiv:0906.3731v3 [astro-ph.HE]

By Giovanni Amelino-Camelia, Lee Smolin

We discuss the prospects for bounding and perhaps even measuring quantum gravity effects on the dispersion of light using the highest energy photons produced in gamma ray bursts measured by the Fermi telescope. These prospects are brigher than might have been expected as in the first 10 months of operation Fermi has reported so far eight events with photons over 100 MeV seen by its Large Area Telescope (LAT). We review features of these events which may bear on Planck scale phenomenology and we discuss the possible implications for the alternative scenarios for in-vacua dispersion coming from breaking or deforming of Poincare invariance. Among these are semi-conservative bounds, which rely on some relatively weak assumptions about the sources, on subluminal and superluminal in-vacuo dispersion. We also propose that it may be possible to look for the arrival of still higher energy photons and neutrinos from GRB's with energies in the range 1014 - 1017 eV. In some cases the quantum gravity dispersion effect would predict these arrivals to be delayed or advanced by days to months from the GRB, giving a clean separation of astrophysical source and spacetime propagation effects.

While the discussed effects on the propagation of photons are extremely tiny and way too feeble to be observable in experiments on Earth, they could add up when the travel is very long distance. In the models the authors consider, the strength of the effect depends on the energy of the photon. The speed of light is then no longer a constant but a function of the energy of the photon. In the low energy limit, photons travel with what we usually call THE speed of light, c [1].

To first approximation there are two cases: either the high energetic photons are faster than the low energetic ones, or the high energetic photons are slower than the low energetic ones. I would have guessed the majority of people had thought if such a scenario is true then the photons with higher energy should be faster. If only because we are secretly all dreaming of traveling faster than the speed of light. But that's not what the data seems to suggest to me.

These scenarios can be tested with signals from gamma ray bursts, highly energetic flashes of light originating in faraway Galaxies. Their spectrum covers a large range of energies. If one records photons of different energies with an exact timing, one can compare their arrival time. In my previous post we had been discussing the gamma ray burst GRB 080916C (the number encodes the date). In this burst, the high energy photons seem to be arriving with a delay relative to the lower energetic ones. However, the statistics of that one burst isn't very convincing. Yes, there was that one lazy high energy photon with 13 GeV that arrived 16.3 seconds after the onset of the burst. And okay, there were a couple more photons that seemed to be delayed, but then the low energy signal had two peaks rather than one. This might have indicated it was a fairly uncommon burst.

However, Giovanni and Lee sifted through some databases and found a couple more gamma ray bursts that were recorded during the last year that show similar characteristics, if not so pronounced. In all cases, the high energetic photons were delayed. Their paper offers a neat table summarizing these events, but unfortunately no statistical analysis for how significant the patterns are.

In the following sections of the paper they constrain several models with that data, most notably those who break and those who only deform Lorentz Invariance. In the first case, the universe has a preferred frame relative to which the energy of the photons is defined. In the second case there is no such preferred frame [2]. They further distinguish between the case where high energetic photons are faster (superluminal) and those in which they are slower (subluminal), and extract bounds on the quantum gravity scale for both cases. It is somewhat unintuitive to extract bounds also on the superluminal case when there is a trend in the data for higher energetic photons to arrive later, but it could be an astrophysical effect that is hiding superluminal propagation. The bounds on the superluminal case however are weaker.

There is quite a lot of astrophysics involved in the emission of these photons and the most conservative explanation for the delay is certainly that the photons were emitted with delay. While Giovianni and Lee's analysis offers useful first estimates, what would be needed is a procedure that allows to cleanly separate astrophysical source effects from effects during propagation. To do so, one had to extract the dependence of the signal on the distance to the source.

In the final section of the paper, Giovanni and Lee suggest to obtain further experimental data by looking for photons of even higher energies (that could be delayed up to months) or neutrinos that are emitted from the same source. In both cases, I wonder whether it is feasible to obtain any sensible statistic within the lifetime of the average physicist.

Altogether it is a very useful paper that summarizes the status. It leaves one wanting though for a more thorough data analysis.

[1] Not to be confused with theories with a varying speed of light which usually means a variation with time, not with energy.

[2] I wrote a paper showing the second case doesn't make sense if you have an energy dependent speed of ligh. You can wind yourself out of my proof by making your theory even weirder.

Imagine there's a war and nobody notices

As you might have read on Peter's blog already, Gil Kalai, a mathematician from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and author of the blog "Combinatorics and More" wrote a book ‘Gina Says,’ Adventures in the Blogsphere String War. It's advertised with the praising remark among others by Elchanan Mossel "I read it when I was sick and couldn’t do other things, and it cheered me up."

Some of you might remember a commenter called "Gina" being omnipresent in the discussions around Peter's book "Not Even Wrong" and Lee's book "The Trouble With Physics". Gil's book summarizes these conversations. I didn't follow them then, and am not tremendously interested to read them now. I have a pdf of the book, but didn't look at it, so don't ask for details. I recall wondering back then though whether Gina is indeed female as the name suggests.

The reason I'm mentioning this is I'm always stunned how people create dramas or 'wars' to lift themselves above irrelevance. The most sensible comment in the discussion came from George Johnson who said "Nobody of the public cares about string theory one way or the other." String theory or any other part of theoretical physics, that carelessness is what really bothers me. And while the question whether string theory is science or religion has indeed received public attention, the mudslinging has shed a very unfortunate light on the way we lead scientific debates.

What dismays me most however is the lax use of the word 'wars'. Science wars, string wars -- we should put our petty arguments a little more into perspective. Some people have real problems. People die in wars every day. They get shot, they are blown into pieces, they lose their children, their homes, their own lives.

We all have the same goal of understanding Nature. And we are in a very privileged position to be able to work towards this goal. Instead of focusing on what divides us we should focus on what we have in common.

Amen.

And a good weekend to all of you.

Some of you might remember a commenter called "Gina" being omnipresent in the discussions around Peter's book "Not Even Wrong" and Lee's book "The Trouble With Physics". Gil's book summarizes these conversations. I didn't follow them then, and am not tremendously interested to read them now. I have a pdf of the book, but didn't look at it, so don't ask for details. I recall wondering back then though whether Gina is indeed female as the name suggests.

The reason I'm mentioning this is I'm always stunned how people create dramas or 'wars' to lift themselves above irrelevance. The most sensible comment in the discussion came from George Johnson who said "Nobody of the public cares about string theory one way or the other." String theory or any other part of theoretical physics, that carelessness is what really bothers me. And while the question whether string theory is science or religion has indeed received public attention, the mudslinging has shed a very unfortunate light on the way we lead scientific debates.

What dismays me most however is the lax use of the word 'wars'. Science wars, string wars -- we should put our petty arguments a little more into perspective. Some people have real problems. People die in wars every day. They get shot, they are blown into pieces, they lose their children, their homes, their own lives.

We all have the same goal of understanding Nature. And we are in a very privileged position to be able to work towards this goal. Instead of focusing on what divides us we should focus on what we have in common.

Amen.

And a good weekend to all of you.

Thursday, June 25, 2009

Author Identifier on the Arxiv

Recently, we discussed author identifiers. The arXiv now offers such an identifier that will be uniquely assigned to you and generate a webpage with your publications. Looks like this. Particularly useful if you have a very common name. Get your own id here; takes about 10 seconds.

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

Who wants tenure anyway?

Tenure. You either hate it or you love it.

www.phdcomics.com

Recently, I had a discussion whether physics is more in need of postdoc or faculty positions. Weird enough, the postdocs present suggested we need more postdocs. As far as I am concerned, the trend to run scientific research increasingly on postdoc positions, non-faculty short-term contracts that are in many cases supervised, is disastrous. I argued many times before short-term contracts favor short-term projects. As a result, ambitious, work-, and time-intensive projects suffer. Besides this, who wants to remain a postdoc forever? Thus, clearly more faculty positions are needed. But tenure?

Some faculty positions are nontenured. The Santa Fe Institute is a prominent example for fixed-term faculty. As you can read in Howard Burton's book, Perimeter Institute initially also didn't have tenure. Meanwhile we do have. The prime reason, I think, is that the sample of top-scientists who will be attracted by a non-tenured position is very limited. While that is a pragmatic reason to offer tenure, it is not an argument in principle.

So lets look at the arguments in principle. Science needs room to breathe. Tenure offers the necessary safety for researchers to work on controversial, risky, or unpopular topics. It gives them the time to run into a dead-end and start over again, without being immediately discarded as failure. It gives them the peace of mind to not worry about their peer's opinion. Safety is, without doubt, essential.

www.sheldoncomics.com

On the downside, safety invites idleness. The impossibility of getting fired doesn't improve neither responsibility nor quality of management or teaching. It is however in my experience the non-research duties that suffer. Peer pressure is sufficient to guarantee profs don't start twiddling thumbs once they are tenured. While tenure would give them the possibility to ignore their peer's ridicule, most take it very seriously. That's no surprise. In expert communities colleagues' approval is important.

macleodcartoons.blogspot.com

In addition, as one of my fellow postdocs put it, a problem with tenure is you'll get stuck with the old guys after they've reached their expiration date. Considering the increasing number of grey hairs on my head, I find this argument borderline to inhuman. Yes, we age. We all do. Yes, with that we lose some abilities, though we might gain others. Throwing out people when they age to improve the output of a workplace creates, frankly, a system I don't want to be part of. The young and the old, they are part of our lives. Ruling out prescribed execution at 42, every one of us goes through these stages. The way to deal with it efficiently is to integrate people according to the stage of their lives.

What remains then is the question how much security is necessary and what time-scales are appropriate to judge on a research program. It is somewhat a mystery to me why academia fails to establish a functioning yet human job system. Let's take Stefan as an example. He decided not to take a postdoc position after his PhD and now works for a scientific publisher. After 2 years with that employer, his contract became permanent. Needless to say, that's not a contract of the do-what-you-want-we-can't-fire-you-anyway sort. It's just a job that can be continued as long as one does it well.

In a recent blogpost at TheScientist Is tenure worth saving?, a commenter summarized his/her problem

Letting people go after a couple of years without any particular reason as to their performance might increase the flux of ideas but it destroys continuity (and, for what it's worth, loyalty). In addition it favors people who are willing to postpone their life possibly until their late thirties or early forties. Which, needless to say, favors men.

In summary, the security tenure offers is an essential ingredient for scientific research. It is not necessarily the only option though. More long- but fixed-term positions, and renewable contracts have similar benefits and would help make academic research a more human career path.

www.phdcomics.com

Recently, I had a discussion whether physics is more in need of postdoc or faculty positions. Weird enough, the postdocs present suggested we need more postdocs. As far as I am concerned, the trend to run scientific research increasingly on postdoc positions, non-faculty short-term contracts that are in many cases supervised, is disastrous. I argued many times before short-term contracts favor short-term projects. As a result, ambitious, work-, and time-intensive projects suffer. Besides this, who wants to remain a postdoc forever? Thus, clearly more faculty positions are needed. But tenure?

Some faculty positions are nontenured. The Santa Fe Institute is a prominent example for fixed-term faculty. As you can read in Howard Burton's book, Perimeter Institute initially also didn't have tenure. Meanwhile we do have. The prime reason, I think, is that the sample of top-scientists who will be attracted by a non-tenured position is very limited. While that is a pragmatic reason to offer tenure, it is not an argument in principle.

So lets look at the arguments in principle. Science needs room to breathe. Tenure offers the necessary safety for researchers to work on controversial, risky, or unpopular topics. It gives them the time to run into a dead-end and start over again, without being immediately discarded as failure. It gives them the peace of mind to not worry about their peer's opinion. Safety is, without doubt, essential.

www.sheldoncomics.com

On the downside, safety invites idleness. The impossibility of getting fired doesn't improve neither responsibility nor quality of management or teaching. It is however in my experience the non-research duties that suffer. Peer pressure is sufficient to guarantee profs don't start twiddling thumbs once they are tenured. While tenure would give them the possibility to ignore their peer's ridicule, most take it very seriously. That's no surprise. In expert communities colleagues' approval is important.

macleodcartoons.blogspot.com

In addition, as one of my fellow postdocs put it, a problem with tenure is you'll get stuck with the old guys after they've reached their expiration date. Considering the increasing number of grey hairs on my head, I find this argument borderline to inhuman. Yes, we age. We all do. Yes, with that we lose some abilities, though we might gain others. Throwing out people when they age to improve the output of a workplace creates, frankly, a system I don't want to be part of. The young and the old, they are part of our lives. Ruling out prescribed execution at 42, every one of us goes through these stages. The way to deal with it efficiently is to integrate people according to the stage of their lives.

What remains then is the question how much security is necessary and what time-scales are appropriate to judge on a research program. It is somewhat a mystery to me why academia fails to establish a functioning yet human job system. Let's take Stefan as an example. He decided not to take a postdoc position after his PhD and now works for a scientific publisher. After 2 years with that employer, his contract became permanent. Needless to say, that's not a contract of the do-what-you-want-we-can't-fire-you-anyway sort. It's just a job that can be continued as long as one does it well.

In a recent blogpost at TheScientist Is tenure worth saving?, a commenter summarized his/her problem

As a young researcher, I spend more and more of my time thinking on why I got into academia in the first place, and sometimes wishes there was a real alternative so I could get out. The problem is that I am now over 30, I haven't had the means (or the 'geographic security') to invest in a house or any of the other things that people I went to school with did 10-15 years ago. As a consequence I am highly educated, but have a very low financial status. This is a cause for stress. At the same time, I will be working on short time contracts for a long while yet, longer even if the administrators get their way. If there is no light at the end of the tunnel, all the smart people will disappear from academia and the universities will end up being schools. This is extremely worrying.

Letting people go after a couple of years without any particular reason as to their performance might increase the flux of ideas but it destroys continuity (and, for what it's worth, loyalty). In addition it favors people who are willing to postpone their life possibly until their late thirties or early forties. Which, needless to say, favors men.

In summary, the security tenure offers is an essential ingredient for scientific research. It is not necessarily the only option though. More long- but fixed-term positions, and renewable contracts have similar benefits and would help make academic research a more human career path.

Sunday, June 21, 2009

Summer Solstice in Germany

This morning at 5:45 UTC was this year's summer solstice: On its annual apparent path across the celestial globe, the Sun has reached its northernmost point. In the northern hemisphere, today is the day of year with the longest period of daylight.

Unfortunately, here in Germany we cannot really enjoy it - it has been grey and rainy most of the time. Here is an interesting view of Germany today, an animation of the pattern of rainfall over three hours in the early evening:

Source: www.wetteronline.de.

Source: www.wetteronline.de.

Colours show precipitation from radar data, coded from light blue for a slight drizzle to magenta for heavy rain. There is a counter-clockwise rotating vortex of clouds, typical for a zone of slight low-pressure, sitting just over Germany. I hope it won't stay there for the rest of the summer.

Unfortunately, here in Germany we cannot really enjoy it - it has been grey and rainy most of the time. Here is an interesting view of Germany today, an animation of the pattern of rainfall over three hours in the early evening:

Colours show precipitation from radar data, coded from light blue for a slight drizzle to magenta for heavy rain. There is a counter-clockwise rotating vortex of clouds, typical for a zone of slight low-pressure, sitting just over Germany. I hope it won't stay there for the rest of the summer.

Thursday, June 18, 2009

Perimeter Institute Grows

We're running out of space! If you visit Perimeter Institute these days, you'll find desks crammed into every single corner in the corridors. Yet, still more people are being hired. One of the hotly discussed topics in the last months has thus been the upcoming building expansion. Luckily noise and dirt will start after I've left. Here is the official press release, with all significant quotes and digits:

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, June 18, 2009 - Today, Neil Turok, Director of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, welcomed the new investment of $10,012,043 from Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) supporting a major expansion of the Institute's world class facility.

"The CFI's support of cutting-edge research infrastructure has transformed Canada's research landscape and increased the country's international competitiveness," said Dr. Eliot Phillipson, President and CEO of the CFI. "Investments like these have allowed Perimeter Institute to become a destination of choice for some of the world's top research talent."

Perimeter's existing building in Waterloo, made possible by a past CFI investment in 2002, exceeded expectations and is operating at capacity. It must now be expanded to achieve the Institute's goal of becoming a world-leading centre promoting major scientific breakthroughs. This new CFI funding will support a 55,000 square foot expansion, in the form of a purpose-built facility designed by the Governor General Award winning firm Teeple Architects.

Plans allow for Perimeter to double its individual and group research spaces, including a new world-class research training space, all with state-of-the-art IT infrastructure enabling complex calculations and the analysis of large data sets as well as remote collaboration with international colleagues. The expanded facility has been designed as the world's ultimate environment for physicists to conceive, visualize and understand the nature of reality, from the subatomic world to the entire universe.

The potential payoff of this expansion of Perimeter Institute is immense. Just one major discovery in theoretical physics is literally capable of changing the world, as when Maxwell discovered a unified description of electricity and magnetism, and Marconi applied his ideas to send the first radio signals. Today, quantum theory is paving the way for the computers and communication systems of tomorrow, which will

vastly exceed the capabilities of current technologies. This historically proven cycle of innovation is fuelled by the foundational thinking that drives the research chain.

"The support received from federal partners like CFI is invaluable and will enable Perimeter Institute to become a leading global hub for theoretical physics research," said Neil Turok, Director of the Institute. "As a result, Perimeter Institute now provides an exceptional opportunity for major scientific progress, for Canada and for the world."

Funding for this project is part of a major $666,128,376 investment announced today by the CFI to support 133 projects at 41 institutions across the country. $247,664,977 was awarded under the Leading Edge Fund (LEF), designed to enable institutions to build on and enhance already successful and productive initiatives supported by past CFI investment.

Another $264,741,466 million was awarded under the New Initiatives Fund (NIF), designed to enhance Canada's capacity in promising new areas of research and technology development. Finally, $153,721,933 was awarded under the Infrastructure Operating Fund, which assists institutions with the incremental operating and maintenance costs associated with new infrastructure.

"Our community is an innovation leader, and we continue to build the intellectual capacity that will drive our future growth and prosperity," said Peter Braid, MP for Kitchener-Waterloo. "This funding for research infrastructure at the Perimeter Institute will ensure that Canada remains at the forefront of scientific discovery, and reinforces our reputation as a centre of excellence."

A complete list of projects funded today by the CFI can be found at: www.innovation.ca.

The Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) is an independent corporation created by the Government of Canada to fund research infrastructure. The CFI mandate is to strengthen the capacity of Canadian universities, colleges, research hospitals, and non-profit research institutions to carry out world-class research and technology development that benefits Canadians.

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, June 18, 2009 - Today, Neil Turok, Director of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, welcomed the new investment of $10,012,043 from Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) supporting a major expansion of the Institute's world class facility.

"The CFI's support of cutting-edge research infrastructure has transformed Canada's research landscape and increased the country's international competitiveness," said Dr. Eliot Phillipson, President and CEO of the CFI. "Investments like these have allowed Perimeter Institute to become a destination of choice for some of the world's top research talent."

Perimeter's existing building in Waterloo, made possible by a past CFI investment in 2002, exceeded expectations and is operating at capacity. It must now be expanded to achieve the Institute's goal of becoming a world-leading centre promoting major scientific breakthroughs. This new CFI funding will support a 55,000 square foot expansion, in the form of a purpose-built facility designed by the Governor General Award winning firm Teeple Architects.

Plans allow for Perimeter to double its individual and group research spaces, including a new world-class research training space, all with state-of-the-art IT infrastructure enabling complex calculations and the analysis of large data sets as well as remote collaboration with international colleagues. The expanded facility has been designed as the world's ultimate environment for physicists to conceive, visualize and understand the nature of reality, from the subatomic world to the entire universe.

The potential payoff of this expansion of Perimeter Institute is immense. Just one major discovery in theoretical physics is literally capable of changing the world, as when Maxwell discovered a unified description of electricity and magnetism, and Marconi applied his ideas to send the first radio signals. Today, quantum theory is paving the way for the computers and communication systems of tomorrow, which will

vastly exceed the capabilities of current technologies. This historically proven cycle of innovation is fuelled by the foundational thinking that drives the research chain.

"The support received from federal partners like CFI is invaluable and will enable Perimeter Institute to become a leading global hub for theoretical physics research," said Neil Turok, Director of the Institute. "As a result, Perimeter Institute now provides an exceptional opportunity for major scientific progress, for Canada and for the world."

Funding for this project is part of a major $666,128,376 investment announced today by the CFI to support 133 projects at 41 institutions across the country. $247,664,977 was awarded under the Leading Edge Fund (LEF), designed to enable institutions to build on and enhance already successful and productive initiatives supported by past CFI investment.

Another $264,741,466 million was awarded under the New Initiatives Fund (NIF), designed to enhance Canada's capacity in promising new areas of research and technology development. Finally, $153,721,933 was awarded under the Infrastructure Operating Fund, which assists institutions with the incremental operating and maintenance costs associated with new infrastructure.

"Our community is an innovation leader, and we continue to build the intellectual capacity that will drive our future growth and prosperity," said Peter Braid, MP for Kitchener-Waterloo. "This funding for research infrastructure at the Perimeter Institute will ensure that Canada remains at the forefront of scientific discovery, and reinforces our reputation as a centre of excellence."

A complete list of projects funded today by the CFI can be found at: www.innovation.ca.

The Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) is an independent corporation created by the Government of Canada to fund research infrastructure. The CFI mandate is to strengthen the capacity of Canadian universities, colleges, research hospitals, and non-profit research institutions to carry out world-class research and technology development that benefits Canadians.

Wednesday, June 17, 2009

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of the Human Brain

Eugene Wigner famously wrote about "The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences"

Though he was indeed speaking about two miracles

Let me highlight two extreme points of view one can take on our ability to describe Nature. Max Tegmark's hypothesis of the "Mathematical Universe" puts forward the idea that mathematics is really all there is, claiming that mathematics is the only thing that is ultimately "free of human baggage". And if we find that counterintuitive or disturbing, that's because our brains didn't evolve to understand the fundamental nature of reality. In fact, according to Tegmark, we should be disturbed if we did not find the fundamental description of reality puzzling.

Let me highlight two extreme points of view one can take on our ability to describe Nature. Max Tegmark's hypothesis of the "Mathematical Universe" puts forward the idea that mathematics is really all there is, claiming that mathematics is the only thing that is ultimately "free of human baggage". And if we find that counterintuitive or disturbing, that's because our brains didn't evolve to understand the fundamental nature of reality. In fact, according to Tegmark, we should be disturbed if we did not find the fundamental description of reality puzzling.

I wrote previously that though the hypothesis can of course stand as such, the justification Tegmark gives is either empty or logically faulty. If one defines what is free of human baggage to be mathematics, then it's an empty statement, thus let's not go there. Without that, we don't know - we can't know - whether mathematics is the only language free of human baggage. It remains possible there exists an even more fundamental language that relates to today's math in a way that today's math relates to narrative. And no, I can't tell you what that would be. But then, our brains didn't evolve to understand...

I actually think Tegmark isn't quite consistent on that point. One the one hand he is defending his hypothesis by saying fundamental reality should seem bizarre to our human brains that evolved to hunt bears, but then the idea that there's something more fundamental than math is too bizarre for him. Do you think 50000 years ago when humans had just begun to use spoken language and to scratch pictures into stones, many of them would have been sympathetic to the idea there's something more powerful than these ingenious achievements of the human mind that allowed them to communicate relations between things without actually pointing at them, and even talk about things that they might have entirely invented?

Now let's look at it from the completely other perspective. A lot of theoretical physicists like to talk about "naturalness," "elegance" or "beauty" of a theory or an equation. These are arguably human judgements and often perceptions that are considerd very important. It is also interesting that, given the required educational background, most people tend to agree on these terms (modulo a deliberate or opportunistic self-deception that financial or peer pressure can create). Whether it is reasonable or not, they do implicitly assume that the human brain has a sense about Nature's ways and that their intuitions will lead them a way to success.

Now let's look at it from the completely other perspective. A lot of theoretical physicists like to talk about "naturalness," "elegance" or "beauty" of a theory or an equation. These are arguably human judgements and often perceptions that are considerd very important. It is also interesting that, given the required educational background, most people tend to agree on these terms (modulo a deliberate or opportunistic self-deception that financial or peer pressure can create). Whether it is reasonable or not, they do implicitly assume that the human brain has a sense about Nature's ways and that their intuitions will lead them a way to success.

I'm not sure why that would be except possibly that after all our brains are made of the same stuff as elementary matter and we are part of the universe we aim to describe and in constant interaction with it. What we are trying to do is to create an accurate image of the universe in our brains, an imperfect repetition of a structure within a structure of that system. Then the question we arrive at is why does the universe evolve to create subsystems that to increasing accuracy mirror the properties of the system? (And, can you continue this self-similarity both up- and downwards?)

Well, needless to say, I can't give you an answer for why the human brain is so unreasonably effective in understanding the laws of Nature. And indeed, spending most of my time between people who believe they have the key to understanding the universe, I sometimes wonder whether our ambitions will continue to deliver insights or whether we'll eventually reach the limits of what we can comprehend, endlessly fooling ourselves into believing we're getting closer to unraveling the fundamentals. But in any case, we're far from reaching that limit. Give it another 50000 years or so.

"The miracle of the appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve."

Though he was indeed speaking about two miracles

"[...] the two miracles of the existence of laws of nature and of the human mind's capacity to divine them."And while a lot has been said and written about the fact that the laws of nature seem to be formulated in the language of mathematics, I always found the larger miracle to be that we simple humans are able to grasp these laws, to write them down, and to use this knowledge to shape Nature according to our liking. As far as mathemetics is concerned, if it wasn't unreasonably effective to that end would we be wondering about it? If mathematics wasn't good to describe the real world it would just be a bizarre form of art with a nerdy cult. The actual question is why is there anything so unreasonably effective that the human brain can comprehend. Understanding, say, cosmological perturbation theory or the representations of Lie Groups isn't such a large survival advantage. (And then there's those who claim we just do it all for the sake of reproduction, obviously.)

I wrote previously that though the hypothesis can of course stand as such, the justification Tegmark gives is either empty or logically faulty. If one defines what is free of human baggage to be mathematics, then it's an empty statement, thus let's not go there. Without that, we don't know - we can't know - whether mathematics is the only language free of human baggage. It remains possible there exists an even more fundamental language that relates to today's math in a way that today's math relates to narrative. And no, I can't tell you what that would be. But then, our brains didn't evolve to understand...

I actually think Tegmark isn't quite consistent on that point. One the one hand he is defending his hypothesis by saying fundamental reality should seem bizarre to our human brains that evolved to hunt bears, but then the idea that there's something more fundamental than math is too bizarre for him. Do you think 50000 years ago when humans had just begun to use spoken language and to scratch pictures into stones, many of them would have been sympathetic to the idea there's something more powerful than these ingenious achievements of the human mind that allowed them to communicate relations between things without actually pointing at them, and even talk about things that they might have entirely invented?

I'm not sure why that would be except possibly that after all our brains are made of the same stuff as elementary matter and we are part of the universe we aim to describe and in constant interaction with it. What we are trying to do is to create an accurate image of the universe in our brains, an imperfect repetition of a structure within a structure of that system. Then the question we arrive at is why does the universe evolve to create subsystems that to increasing accuracy mirror the properties of the system? (And, can you continue this self-similarity both up- and downwards?)

Well, needless to say, I can't give you an answer for why the human brain is so unreasonably effective in understanding the laws of Nature. And indeed, spending most of my time between people who believe they have the key to understanding the universe, I sometimes wonder whether our ambitions will continue to deliver insights or whether we'll eventually reach the limits of what we can comprehend, endlessly fooling ourselves into believing we're getting closer to unraveling the fundamentals. But in any case, we're far from reaching that limit. Give it another 50000 years or so.

Sunday, June 14, 2009

Shrinking Betelgeuse

This is news I can't let uncommented, after all my recent posts about interferometry: In a recent Astrophysical Journal Letter, a team of astronomers lead by Charles H. Townes, Nobel laureate for his contribution to the development of the laser, report "A Systematic Change with Time in the Size of Betelgeuse".

Betelgeuse, or α Orionis, is the bright red star in the shoulder of the constellation Orion. In 1921, Albert Michelson and Francis Pease succeeded in measuring its diameter as about 50 milliarcseconds (mas), using an interferometer mounted onto the main telescope of Mount Wilson observatory. This was the first time the diameter of a star could be measured. 50 milliarcseconds is a tiny angle, corresponding roughly to the apparent size of an object 100 metres big on the Moon. But given the distance to Betelgeuse, this means the star, when put in the place of the Sun, would fill the solar system up to the orbit of Jupiter.

In the meantime, Betelgeuse could be resolved directly using the Hubble space telescope, and its distance measured to be 200 parsecs (650 light years), though there remains an uncertainty of about 25 percent. And it has been the object of many interferometric studies.

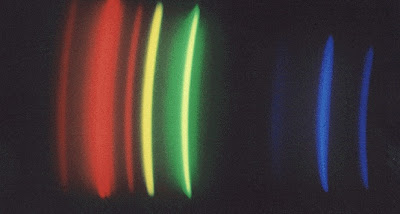

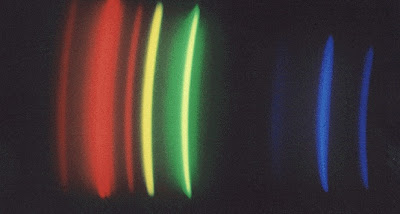

But given the diffuseness of the outer limits of this Red Supergiant star, which on average has a density less than 1/10000 the density of air, measurements of its diameter depend on the wavelength of observation, as the thin outer atmosphere has different transparency for different wavelengths. Here is a comparison of the shape of Betelgeuse, as reconstructed from interferometric measurements taken within two weeks at three different wavelengths in the infrared:

Source: Surface imaging of Betelgeuse with the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST) and the William Herschel Telescope (WHT).

Source: Surface imaging of Betelgeuse with the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST) and the William Herschel Telescope (WHT).

The two images on the right were reconstructed using data from the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST), and the image on the left with data from the William Herschel Telescope (WHT). Each image has a side length corresponding to 100 mas, and one sees big differences in the diameter of the star, and of its surface features, depending of the wavelength at which it is observed.

This fact makes it difficult to compare directly angular diameters of Betelgeuse obtained with different instruments at different wavelengths. Now, the letter of Charles Townes' team reports on data collected with one instrument at one wavelength over the last 15 years. Using the Infrared Spatial Interferometer (ISI) on Mount Wilson, not far from where Michelson and Pease did their pioneering work, they observe at a wavelength of around 11000 nanometres, and write:

The diameters measured by the ISI are not particularly inconsistent with previous measurements, are rather accurate, and show clearly that the star has systematically decreased in size by about 15% over the past 15 years.

(Click for larger view – data from Townes et al., APJ Lett 697 (2009) L127-L128)

(Click for larger view – data from Townes et al., APJ Lett 697 (2009) L127-L128)

The graph shows their data (note that the zero-line is suppressed, so the change appears bigger than it actually is), together with a best fit by a parabola in grey, and the Michelson & Pease result in orange. Michelson and Pease estimated that the actual diametre of Betelgeuse could be larger by 10%-15% because of systematic errors in their measurement method. I have added the line in magenta, which shows, for comparison, the radius of the orbit of Jupiter, using the latest Hipparcos/VLA parallax distance to Betelgeuse to convert angles in actual distances.

Betelgeuse has been known to be a star with variability, but it seems that this change in size is odd and unexpected, even more so as its luminosity has been roughly constant. It's fascinating to me that such a change can be measured. As the APJ Letter concludes:

ISI measurements over the last 15 years clearly show a systematic change in the diameter of α Ori. This change may or may not be periodic; if it is, the period is likely rather long, perhaps a few decades. [...] It should be valuable to continue accurate measurements of α Ori's size and other characteristics in order to understand the dynamics involved in this striking change, and to have systematic long-term measurements of similar stars.

Betelgeuse, or α Orionis, is the bright red star in the shoulder of the constellation Orion. In 1921, Albert Michelson and Francis Pease succeeded in measuring its diameter as about 50 milliarcseconds (mas), using an interferometer mounted onto the main telescope of Mount Wilson observatory. This was the first time the diameter of a star could be measured. 50 milliarcseconds is a tiny angle, corresponding roughly to the apparent size of an object 100 metres big on the Moon. But given the distance to Betelgeuse, this means the star, when put in the place of the Sun, would fill the solar system up to the orbit of Jupiter.

In the meantime, Betelgeuse could be resolved directly using the Hubble space telescope, and its distance measured to be 200 parsecs (650 light years), though there remains an uncertainty of about 25 percent. And it has been the object of many interferometric studies.

But given the diffuseness of the outer limits of this Red Supergiant star, which on average has a density less than 1/10000 the density of air, measurements of its diameter depend on the wavelength of observation, as the thin outer atmosphere has different transparency for different wavelengths. Here is a comparison of the shape of Betelgeuse, as reconstructed from interferometric measurements taken within two weeks at three different wavelengths in the infrared:

The two images on the right were reconstructed using data from the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST), and the image on the left with data from the William Herschel Telescope (WHT). Each image has a side length corresponding to 100 mas, and one sees big differences in the diameter of the star, and of its surface features, depending of the wavelength at which it is observed.

This fact makes it difficult to compare directly angular diameters of Betelgeuse obtained with different instruments at different wavelengths. Now, the letter of Charles Townes' team reports on data collected with one instrument at one wavelength over the last 15 years. Using the Infrared Spatial Interferometer (ISI) on Mount Wilson, not far from where Michelson and Pease did their pioneering work, they observe at a wavelength of around 11000 nanometres, and write:

The diameters measured by the ISI are not particularly inconsistent with previous measurements, are rather accurate, and show clearly that the star has systematically decreased in size by about 15% over the past 15 years.

The graph shows their data (note that the zero-line is suppressed, so the change appears bigger than it actually is), together with a best fit by a parabola in grey, and the Michelson & Pease result in orange. Michelson and Pease estimated that the actual diametre of Betelgeuse could be larger by 10%-15% because of systematic errors in their measurement method. I have added the line in magenta, which shows, for comparison, the radius of the orbit of Jupiter, using the latest Hipparcos/VLA parallax distance to Betelgeuse to convert angles in actual distances.

Betelgeuse has been known to be a star with variability, but it seems that this change in size is odd and unexpected, even more so as its luminosity has been roughly constant. It's fascinating to me that such a change can be measured. As the APJ Letter concludes:

ISI measurements over the last 15 years clearly show a systematic change in the diameter of α Ori. This change may or may not be periodic; if it is, the period is likely rather long, perhaps a few decades. [...] It should be valuable to continue accurate measurements of α Ori's size and other characteristics in order to understand the dynamics involved in this striking change, and to have systematic long-term measurements of similar stars.

- Townes, C. H.; Wishnow, E. H.; Hale, D. D. S.; Walp, B.: Systematic Change with Time in the Size of Betelgeuse, The Astrophysical Journal Letters 697 (2009) L127-L128.

- Press release Red giant star Betelgeuse mysteriously shrinking.

- The U.C. Berkeley Infrared Spatial Interferometer Array

- Surface imaging of Betelgeuse with the Cambridge Optical Aperture Synthesis Telescope (COAST) and the William Herschel Telescope (WHT)

- Variable Star of the Month, December 2000: Alpha Orionis

Friday, June 12, 2009

Quantum To Cosmos

Today Perimeter Institute announced the “Quantum to Cosmos: Ideas for the Future” festival that will take place October 15 to 25. And I'm so sorry I can't be here because it sounds tremendously exciting! The most important thing first: there is a website where you can find a lot of information

This afternoon in the Theater of Ideas, after a welcome by our director Neil Turok, John Matlock (Director of Communications) and Richard Epp (Scientific Outreach) briefly outlined the event, followed by several VIPs in suits who said a lot of nice words, including the mayor of Waterloo, two guys who are ministers of something, a women from TVO, and Mike Lazaridis himself.

The Quantum to Cosmos festival will celebrate the 10th anniversary of PI’s inception, and simultaneously contribute to Canada’s National Science & Technology week, and be part of the International Year of Astronomy. As Mike added later, it isn't only PI's 10th anniversary, but also the 10th anniversary of the BlackBerry.

There are more than 50 events planned, including exhibits, cultural performances and film screenings, plus there will be quite an effort be made to allow a larger online community to take part in the festival by providing podcasts, live streaming and live blogging, supported by the media partner TVO. The festival is on Facebook, on Twitter on MySpace and on Friendfeed. A lot of interesting speakers will be here for the event, including Larry Abbott, Sean Carroll and Katherine Freese.

After the announcement we had a reception in the atrium. The guy with the camera has been sneaking around

and I took a couple of photos. Here is Neil waving with his arms

Robin Blume-Kohout and Achim Kempf

And here you can make a little bit of crowd-spotting. In the picture: two of our faculty members, Rob Spekkens and Rob Myers, Jon Henson, Dario Benedetti, the mayor of Waterloo, Simone Speziale, Constantinos Skordis, Samuel Vazquez, Nicolas Menicucci, and, so I belive, Jon Walgate.

(Close-up of the two Robs here). And here is the charme of the Institute, Sarah Croke, who is presently also our Postdoc Representative

I am afraid I will miss them all.

This afternoon in the Theater of Ideas, after a welcome by our director Neil Turok, John Matlock (Director of Communications) and Richard Epp (Scientific Outreach) briefly outlined the event, followed by several VIPs in suits who said a lot of nice words, including the mayor of Waterloo, two guys who are ministers of something, a women from TVO, and Mike Lazaridis himself.

The Quantum to Cosmos festival will celebrate the 10th anniversary of PI’s inception, and simultaneously contribute to Canada’s National Science & Technology week, and be part of the International Year of Astronomy. As Mike added later, it isn't only PI's 10th anniversary, but also the 10th anniversary of the BlackBerry.

There are more than 50 events planned, including exhibits, cultural performances and film screenings, plus there will be quite an effort be made to allow a larger online community to take part in the festival by providing podcasts, live streaming and live blogging, supported by the media partner TVO. The festival is on Facebook, on Twitter on MySpace and on Friendfeed. A lot of interesting speakers will be here for the event, including Larry Abbott, Sean Carroll and Katherine Freese.

After the announcement we had a reception in the atrium. The guy with the camera has been sneaking around

and I took a couple of photos. Here is Neil waving with his arms

Robin Blume-Kohout and Achim Kempf

And here you can make a little bit of crowd-spotting. In the picture: two of our faculty members, Rob Spekkens and Rob Myers, Jon Henson, Dario Benedetti, the mayor of Waterloo, Simone Speziale, Constantinos Skordis, Samuel Vazquez, Nicolas Menicucci, and, so I belive, Jon Walgate.

(Close-up of the two Robs here). And here is the charme of the Institute, Sarah Croke, who is presently also our Postdoc Representative

I am afraid I will miss them all.

With that, I wish you all a great weekend!

Thursday, June 11, 2009

This and That

Some photos from the SUSY 2009 conference are online now, you can find them here. Here is one that caught me at the reception first day. And just in case, I'm the second from the left. Please don't ask me who these people are coz my brain has a black hole where other people store names.

Some more photos that I made, here's Boston

And here's the Curry Student Center at Northeastern University, the building where the parallel sessions took place, as well as some folks in the coffee break and the audience of the public lecture

I'm not on the group photo for no other reason than that I didn't know when it would be made.

Some other things:

Some more photos that I made, here's Boston

And here's the Curry Student Center at Northeastern University, the building where the parallel sessions took place, as well as some folks in the coffee break and the audience of the public lecture

I'm not on the group photo for no other reason than that I didn't know when it would be made.

Some other things:

- Lee Smolin wrote a piece for PhysicsWorld titled "The Unique Universe". I don't know what to make out of it, so I'll restrain from commenting.

- Martin Fenner asks Why do we go to conferences.

- For quite convoluted reasons I found this article about Perimeter Institute in the Google cache. It's hilarious. I have the uncanny feeling somebody might be quiet unhappy I digged it out, but I can't resist sharing it. Let me quote you some lines

Faced with [Laurent] Freidel’s delirious state of distraction, his wife reportedly pleaded with a colleague: “Can’t you do something? He’s going insane.” [...]

Markopoulou-Kalamara is the only female faculty member at Perimeter. She makes efforts to tone down her exuberant European elegance to match the company she keeps—that is, variously aggressive, cavalier and nerdy male physicists. One of them, her husband Olaf Dreyer, had recently experienced an eureka moment. “He thinks he’s found the solution to quantum gravity,” she says. “He’s flipping out.” [...]

Every physicist at Perimeter has free use of a BlackBerry, though, as Smolin laments, “the phone bill isn’t covered.” [...]

Bilson-Thompson, 33, is a playful scientist who wears a perennial pony-tail and fleece [...] The Perimeter Institute, he says, encourages the same adventuresome pursuit of knowledge with a simple laissez-faire formula: “Take scientists, put them in a box and say, ‘OK you boffins, do your thing.’” [...]

Physicists are forever thinking they’ve “got it,” Markopoulou-Kalamara says. Or they are tormented because they don’t. This is the physicist’s bipolar yo-yo of euphoria and despair. “We need to have a psychiatrist in residence,” she says. “Somebody is always in a state of crisis over something.” [...]

As for Smolin, he said “Hello” when Susskind arrived for his visit at Perimeter in March, but got a tepid response. “It was in a tone that gave me the impression he had no interest in speaking to me,” he says.

Says Susskind, “I spend every day having lots of interesting conversations.” [...]

See what fun it is to be a theoretical physicist?

Sunday, June 07, 2009

Hello from the SUSY 2009

As previously mentioned, I am here in Boston at the SUSY 2009, the 17th International Conference on Supersymmetry and the Unification of Fundamental Interactions. Since its inception 1993, the SUSY has become the meeting for everything around and everybody involved in physics beyond the Standard Model, from Supersymmetry and its breaking, via extra dimensions of any sort (large, universal, warped), String model building in general to Grand Unification and the phenomenology of Quantum Gravity (though mostly focussed on graviton and black hole production at the LHC). What was previously called the session on "alternatives" is now called "unconventional approaches." The word "alternative," it seems, is a bit worn out. The SUSY is a lively mix of experiment with theory, which is one of the reasons why I like it.

The meeting this year takes place at Northeastern University, where I had not been before. It is a nice place, very conveniently located, with a small but well maintained campus. (I took some photos, but unfortunately forgot the cable I need to upload them, so they will follow later). I had not known that Northeastern University was also where the first SUSY conference in 1993 was held.

On Friday we had the first session of plenary talks with updates from the LHC and TeVatron, and a reception in the evening to get to say hello to familiar and unfamiliar faces. Every time I'm at the SUSY there seem to be more people. Maybe it's me getting old, but there are really a lot of young postdocs around this year many of whom are enthusiastic about their research and I'm sure they will make interesting contributions during their career. Most of them were crammed in the parallel sessions during the weekend. I too delivered my talk this afternoon (slides here), squeezed between SUSY breaking and degenerate vacua. I think it went reasonably well.

This evening, we also had a public lecture by Frank Wilczek from MIT (Nobel Prize 2004 together with David Gross and David Politzer). Titled "Anticipating a New Golden Age," Wilczek explained what the LHC (The World's Largest Microscope) is and what it does, including the LHC Rap. He then went on to explain what Supersymmetry is and how it helps with the unification of the gauge couplings, expressing his conviction that Nature is giving us a clear sign that Supersymmetry is part of her workings (that part of the talk being identical to what he told at SciFoo last summer). He finished with the inspirational note that it's not only an exciting time to be a physicist, but an exiting time to be a thinking being - even if you are not actively working on these theories, we might be very close to unraveling some fundamental truth about reality. It was a very nice talk and I think the audience enjoyed it.

The meeting this year takes place at Northeastern University, where I had not been before. It is a nice place, very conveniently located, with a small but well maintained campus. (I took some photos, but unfortunately forgot the cable I need to upload them, so they will follow later). I had not known that Northeastern University was also where the first SUSY conference in 1993 was held.

On Friday we had the first session of plenary talks with updates from the LHC and TeVatron, and a reception in the evening to get to say hello to familiar and unfamiliar faces. Every time I'm at the SUSY there seem to be more people. Maybe it's me getting old, but there are really a lot of young postdocs around this year many of whom are enthusiastic about their research and I'm sure they will make interesting contributions during their career. Most of them were crammed in the parallel sessions during the weekend. I too delivered my talk this afternoon (slides here), squeezed between SUSY breaking and degenerate vacua. I think it went reasonably well.

This evening, we also had a public lecture by Frank Wilczek from MIT (Nobel Prize 2004 together with David Gross and David Politzer). Titled "Anticipating a New Golden Age," Wilczek explained what the LHC (The World's Largest Microscope) is and what it does, including the LHC Rap. He then went on to explain what Supersymmetry is and how it helps with the unification of the gauge couplings, expressing his conviction that Nature is giving us a clear sign that Supersymmetry is part of her workings (that part of the talk being identical to what he told at SciFoo last summer). He finished with the inspirational note that it's not only an exciting time to be a physicist, but an exiting time to be a thinking being - even if you are not actively working on these theories, we might be very close to unraveling some fundamental truth about reality. It was a very nice talk and I think the audience enjoyed it.

Thursday, June 04, 2009

This and That

Combining waves can make for quite spectacular effects. The June edition of Physics Today has two interesting articles available for free describing such situations:

- In Probing stars with optical and near-IR interferometry, Theo ten Brummelaar, Michelle Creech-Eakman, and John Monnier explain how "new high-resolution data and images, derived from the light gathered by separated telescopes, are revealing that stars are not always as they seem." Now, the combination of radio telescopes to synthesize huge telescope apertures and gain the corresponding angular resolution is a well-established technique.

But adding interferometrically the wave crests of visible light from a star collected in two separate telescopes is a more recent development. Performing some Fourier transforms results in images with an angular resolution of milli arcseconds - enough to see a human on the moon, or to resolve the size and shape of stars.

Altair in the constellation Aquila, about twice as big as the Sun and 18 light years away, is rotating rapidly so that it is flattened. The image on the right has been created using interferometry with light waves. Credit: Ming Zhao (University of Michigan), from Imaging the Surface of Altair, John D. Monnier et al, arXiv:0706.0867v2. - Ocean waves are generated by fluctuating wind pressure on the water surface. Due to the dispersion of the phase velocity (longer waves run faster) and a weak interaction between different waves transferring energy to longer waves, dominant waves are the bigger the stronger and longer the wind blows. Together with the effect of opposing ocean currents, very big waves can emerge. In Rogue waves, Chris Garrett and Johannes Gemmrich look at the "rich and challenging physics [...] behind the gigantic ocean waves that seem to appear without warning to damage ships or sweep people off rocky shores."

Rogue wave in the Bay of Biscay, France. Credit: NOAA Photo Library, via Wikipedia.

Wednesday, June 03, 2009

Upcoming Conferences

I'll be traveling quite a bit in the coming months. The next days I am in Boston at the SUSY '09. In July I'm at the FQXi conference in Ponta Delgada. I meant to go to the Marcel Grossman meeting in Paris, but they still haven't managed to let me know whether my talk was accepted. Meanwhile, there is no way I will ever get a hotel room around July 14th in Paris, so I won't be going. (If you are involved with the organization of that meeting, shame on you.) I'm considering to go to the "Quantum to Cosmos" meeting in Bremen, but haven't yet made up my mind, and later I'll be at the Atlanta Conference on Science and Innovation Policy in, oohm, Atlanta I guess. Besides that I will probably be busy with my upcoming move.

For my recent trip to Denver I obviously forgot that visitors to the USA are now supposed to apply online for a "travel authorization." Thus, a dismayed officer left an url in my passport to remind me to fill out the webform in a timely manner for my next trip. After I figured the ESTA website doesn't load at all with Google Chrome, I indeed managed to submit the relevant data and hope to have a smooth trip.

Should our paths cross at any of these places, it is always nice to meet readers, so don't hesitate to say hello!

Ooops, just read the registration fees for the Bremen meeting, I'm not going.

For my recent trip to Denver I obviously forgot that visitors to the USA are now supposed to apply online for a "travel authorization." Thus, a dismayed officer left an url in my passport to remind me to fill out the webform in a timely manner for my next trip. After I figured the ESTA website doesn't load at all with Google Chrome, I indeed managed to submit the relevant data and hope to have a smooth trip.

Should our paths cross at any of these places, it is always nice to meet readers, so don't hesitate to say hello!

Ooops, just read the registration fees for the Bremen meeting, I'm not going.

Tuesday, June 02, 2009

Public Display of Attention