On a recent flight I was reading Jaron Lanier's book

You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto. I got stuck somewhere in the middle and then dozed off watching

Avatar. (Brilliant. Best movie I've seen for a long time, even on a tiny in-seat monitor.) This combination got me thinking about a common theme in both: collective intelligence. Lanier is a skeptic. He writes

“The intentions of the cybernetic totalist tribe are good. They are simply following a path that was blazed in earlier times by well-meaning Freudian and Marxists [...] A self-proclaimed materialist movement that attempts to base itself on science starts to look like a religion rather quickly [...] The Singularity and the noospehre, the idea that a collective consciousness emerges from all the users on the web, echo Marxist social determinism and Freud's calculus of perversion.”

And later, in a section “Why It Matters,” he writes “Emphasizing the crowd means deemphasizing individual humans in the design of the society.”

I am very sympathetic to many points Lanier is making, but I dislike the “Manifesto”-style in which he's trying to lead his arguments. In any case, should I make it to the end of his book, I'll write a review. For now however, I want to focus on the topic of collective intelligence, for despite all the words Lanier is quite fuzzy on the use of terminology. I started wondering: What do people actually mean when they talk about collective intelligence? Are they really all talking about the same thing? I came to the conclusion that there's two different notions of collective intelligence, and I thought I'd amuse you with writing about a topic that I know pretty much nothing about.

Setting the StageFirst, let us be clear on what we're talking about: A collective or a group or a crowd will in the following simply be a set with elements. The elements of that set operate on input and create output. I will refer to the input and output likewise as “knowledge.”

I further do not actually want to talk about the “intelligence” of a collective in the common sense for two reasons. One is that a collective can be intelligent one day and stupid the next day. I'd rather focus on one particular process the collective makes instead of assigning a qualifier to it as a whole. A process could be a decision as well as a direct action. Second reason is that using the term intelligent isn't useful without defining it. Thus, I would instead like to talk about collective processes that are beneficial for the collective. That's basically because I don't think measures like the IQ are particularly meaningful to assess intelligence since they also test for knowledge. Sure, the both are in humans correlated with each other because both draw upon the functionality of the same brain, but in principle it's different things: The one, knowledge, is the input a system has to work with, the other one, intelligence, is the procedure by which the input is processed. Clearly, to make good decisions both is needed. That's true for individuals as much as for groups. Consequently, to make beneficial decisions the collective needs to be well-informed as well as have a good way to process that information. Googeling doesn't make you more intelligent. It gives you more information.

Thus, what I will mean in the following with “collective intelligence” is the ability of a set of elements operating on some input to perform processes that are beneficial for the collective. Note that you'll have to define what your set is before you can make any statements. I know, it sounds pretty abstract, but it will be useful in its generality for the following.

Collective Intelligence Type I

The first sort of collective intelligence is simply the gain in knowledge that you can get when you bring many elements of your set together. If every element brings some knowledge, you've now trivially more knowledge together. But that isn't the interesting aspect. The interesting aspect is that you can give the elements of your set the possibility to operate on each other's output, which means that you can create more knowledge than you could have done had they be disconnected.

There's many examples for this sort of collective knowledge. It's what you count on if you bring smart people together and let them talk to each other. They'll exchange ideas, they will build on each others' conclusions, and that way they can produce something genuinely new, say, a groundbreaking paper. I'll count that as a process that's beneficial for the collective.

(A recent meeting of this sort is this one, report unfortunately in German.) It is this sort of collective intelligence that has become vastly easier to make use of with the internet, web2.0 and other advances of information technology. It is much easier today than it was two decades ago to give people with shared interests a platform to exchange their ideas.

Note that I carefully wrote that you

can get a gain of knowledge by better connectivity. It is however not a given. Just providing a possibility to share knowledge is not necessarily a way to arrive at a good decision, conclusion, or even useful creation of knowledge. Under certain circumstances, too much sharing of knowledge actually dumbs down a group because it reduces heterogeneity. Besides, human cognitive processes are messy and affected by all sorts of biases. As a consequence, the benefit of sharing knowledge depends on how the knowledge is shared, for example because judgement about the truth-value of a piece of knowledge is often dependent on the source it came from. These are some pitfalls that Surowiecki pointed out in his book

The Wisdom of Crowds (

read my review here). To exploit the additional knowledge gain you get from connecting groups of people you thus have to do some research about the effects and side-effects of social interactions.

You, and you, and you and I, we are some sort of collective and we exchange knowledge. If you give me a piece of information that's useful for my work or if you learn something from me, it's beneficial and I would argue we're thus part of an collective intelligence in that sense. Clearly, the internet has opened a vast potential for this. There's all sorts of unused possibilities in connecting billions of people online which we have only begin to explore. However promising, this sort of collective intelligence is at the same time of a very trivial sort. We're not actually doing anything new here. People have talked to each other and exchanged ideas as long as humans have wondered how to best skin a bear. The difference is just that now we're connecting more people faster and easier.

A mathematical example for this sort of collective intelligence is a group with some basis elements and operators acting on them to create the full group. The basis elements are in this case the knowledge you start with. The operators are the collective. If you only allow each operator to repeatedly act on the same element (his own “knowledge”) you'll generate only a small part of what you'll generate if you allow all operators to act on all elements (use all knowledge).

Collective Intelligence Type II

The first type of collective intelligence is common and readily found in human groups, but in my opinion actually not the interesting type. The interesting type of collective intelligence is one in which knowledge is created by the collective as a whole and not by any of its elements. An example for that is your brain. Your brain is some sort of collective. It consists of neurons that process input and create output. Yet the thought processes that allow you to make conclusions are circuits in your brain that are not assigned to any specific neuron. The steps of your decision can not be broken down to processes on the elements simply because they don't exist on that level. Your intelligence is a truly emergent feature. It doesn't make sense on the level of a neutron.

Note how very different this is to the first example of bringing together elements that create knowledge individually. The first type of collective intelligence is very common among human groups, the latter isn't. Wikipedia is an example of the first sort of (trivial) collective intelligence: It thrives from adding up the knowledge of many individuals. It doesn't actually collectively create anything truly new. The same is the case for crowdsourcing: Posing a problem to a large group of people allows you to use all their knowledge as well as their intelligence. Yet you're not creating anything that wasn't previously there already.

A simple example of actual collective intelligence of type II is the starting point of Surowiecki's book. Have a group of people estimate something like the number of marbles in a jar or the weigh of an ox or something like that. Then take the average value. It will generally give a pretty good result, basically because individual errors average out. (This is an example that does not work well if you allow people to exchange their guesses in advance, it will skew the result. Recall above cautionary note about how to exploit collective wisdom.) What's new here is that one has added a process that was not previously there, a procedure to aggregate individual knowledge other than just adding it up. Note here that it's relevant to first define what you mean with the collective you're talking about before you decide what sort of intelligence you're dealing with. You could easily enough add Bob to your ox-estimating group and what Bob does is that he asks everybody for their guess and takes the average value. Now who is intelligent: Bob or the group? It would depend on whether you did count Bob with his input processing as being part of the group originally, so one has to be precise. Anyway, in this simple case one is just taking an average value, not a very sophisticated aggregation of knowledge, but there are less trivial cases.

For example our economic system, according to the standard general equilibrium theory, the well-known interplay of supply and demand that, ideally, results in pricing products in such a way that the economy runs maximally efficient. The equilibrium that one works towards is not something known by anybody participating in that system. The aggregation mechanism is a free market economy. Now one can debate how well that actually works and under which circumstances the model doesn't apply, but that's not really the point here. The point is that this “invisible hand” of optimization is a features that adds something truly new, some intelligence that is not present on the individual level.

Other examples for human collectives are arguably political decision making processes. Again, one can debate how well these work and how beneficial the outcome really is, more research is clearly needed, but it suffices to say here that at least they work better than nothing at all. The thing is however that for human collectives you need some mechanism to bring back the insight gained from the aggregate to the individual level, either by communicating the result of a decision or directly by converting it into an action or recommendation. Just leaving it standing inaccessibly at the aggregate level isn't useful because actions are still made by the individuals.

I want to add another example of human collectives here which is the academic system. In the academic system we do not have written down rules to aggregate knowledge, neither do we have a model for how it works. However, if you look at the history of science, we nevertheless de facto have some aggregation mechanism. It's not like there was ever a vote whether or not Coulomb's (wrong) magnetic field law should be kept in the textbooks, yet here we are without it. I think Smolin in his book

The Trouble with Physics (

read my review here) summarized it well:

“Science has succeeded because scientists comprise a community that is defined and maintained by adherence to a shared ethics.”

The shared ethics Smolin is talking about is basically some sort of scientific method. Again one can debate whether Smolin's suggestion is the best way to set up the system, but that isn't the point here. He's right in that, written law or not, scientists have used some sort of ethics and that's what made the scientific community more than just a bunch of smart people. It has created a solid and growing body of knowledge that spreads though educational systems and is the driver of innovation. Note however that this sort of collective intelligence does not create a theory, it (ideally) merely singles out the ones to be kept.

Another example for this sort of collective intelligence outside the human realm

is the DNA of the bacterium Escherichia Coli containing information in its topology and not only in its sequence. That's not some “knowledge” that any of the elements of the DNA string encodes - it can only be read off from the whole string. An example of the mathematical sort might be a manifold. Consider every point of the manifold the knowledge and parallel transport by some infinitesimal step the elements of your collective. If you only look at the local surrounding you'll never figure out additional information in the topology of the whole thing. You'll have to do something more for that, like looking for closed loops.

LimitationsClearly for me as a scientist the interesting question is what can collective intelligence do for scientific progress. I think we're doing well with the first type of collective intelligence. It is frequently used. The second type of intelligence is however one that does not exist for the creation of scientific knowledge and I am not sure it ever will.

What would it mean, this collective intelligence of type 2 in science? Consider a large group of scientists, maybe thousands, working on a notoriously difficult problem, possibly for decades. They'll collect and publish many pieces of knowledge. Collective intelligence of type 2 would be an aggregation process not working on the individual level that finds a solution to this difficult problem from the pieces scientists have found. However, the aggregation process that commonly worked for this is an individual finding the right pieces and being able to draw the right conclusions, thus type 1 of collective intelligence. Remember what I said earlier, as long as our society is run by the actions of individuals you need some way to bring back collective knowledge to the individual level, otherwise it's useless. But what mechanism do we have for that in science other than a scientist?

There are some few cases in which indeed scientific conclusions have been drawn by aggregation of accumulated knowledge. For example finding relations between seemingly distinct (medical) topics from citation analysis. But these examples are rare and I'm not sure how far one can ever get with this. This then opens the following question: Can it happen that we will not be able to arrive at some insights simply due to the limitations of the human brain to recognize knowledge that is not present at the individual level? And what is the next step of evolution? Can we ever go beyond that?

(Related: See also my post

We are Einstein)

SummaryI've argued there's two types of collective intelligence: One in which bringing together elements of a group and connecting them creates output that was not possible to create without the connections. In this case however, the output is still created by the single elements, it's just that the connections allow more of it and thus making them can open unused potential. This is the trivial, type 1, sort of collective intelligence. The second, more interesting, sort of collective intelligence one has when the knowledge is not present at the individual level at all. It is contained on the collective level, and its production cannot be assigned to any element of the group in particular.

For what groups of humans are concerned, the first sort of collective intelligence is already well in use and with a better understanding of social dynamics and psychology we will be able to exploit more unused potential. For what the second type is concerned, I think one should rightfully be skeptic. It is questionable how much can be achieved by it, and unclear how it can be created or used. We're a long way from global collective intelligence like that connecting the lifeforms on Pandora.

In his book, Lanier offers the reader a list with suggestions for “what each of us can do” featuring the item “Write a blog post that took weeks of reflection before you heard the inner voice that needed to come out.” Well, I report that I've been reflecting on this for some weeks, though not continuously. After all, I have a job to do. My inner voices are typically busy with some other things than wanting to come out, like reminding me I should put the laundry into the dryer now. In any case, I hope it won't take you several weeks to read it ;-)

Yesterday, Stefan and I went to see the "Body Worlds" exhibition, which is currently in Offenbach, close to Frankfurt, Germany. Body Worlds is a traveling exhibition that displays human bodies and body parts that have been preserved using a technique called plastination. Basically, it works by removing all bodily fluids and fat from the tissue by washing it out with acetone, and then replacing these fluids with silicone. That is to say, the exhibits are not anatomic models but actually real. The method of plastination used for these purposes was invented by Gunther von Hagens, then at the University of Heidelberg. His work there likely was inspiration for the horror movie "Anatomy," starring Franka Potente, which still causes me the occasional nightmare.

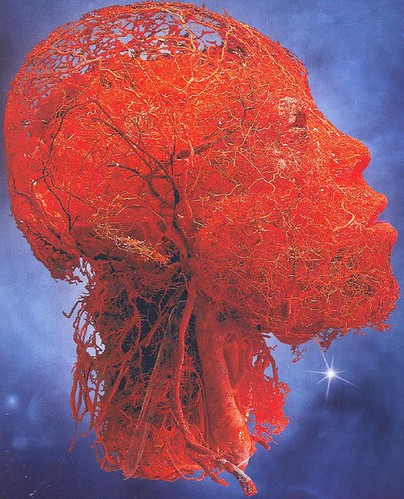

Yesterday, Stefan and I went to see the "Body Worlds" exhibition, which is currently in Offenbach, close to Frankfurt, Germany. Body Worlds is a traveling exhibition that displays human bodies and body parts that have been preserved using a technique called plastination. Basically, it works by removing all bodily fluids and fat from the tissue by washing it out with acetone, and then replacing these fluids with silicone. That is to say, the exhibits are not anatomic models but actually real. The method of plastination used for these purposes was invented by Gunther von Hagens, then at the University of Heidelberg. His work there likely was inspiration for the horror movie "Anatomy," starring Franka Potente, which still causes me the occasional nightmare. Besides many whole-body exhibits in fancy positions - dancing, playing saxophone, jumping over fences, during intercourse (must be 16 or older to see that) - they had all organs separately, some showing various illnesses and diseases (fatty liver, cancerous uterus, smoker's lung), as well as artificial joints. Some of the organs were cut into small slices or into half, so you could see inside. It is quite amazing really, to see all the muscles, bands, and nerves. Most stunning I found the capillary system that leaves behind the shape of the body after plastination (see picture to the left, more here).

Besides many whole-body exhibits in fancy positions - dancing, playing saxophone, jumping over fences, during intercourse (must be 16 or older to see that) - they had all organs separately, some showing various illnesses and diseases (fatty liver, cancerous uterus, smoker's lung), as well as artificial joints. Some of the organs were cut into small slices or into half, so you could see inside. It is quite amazing really, to see all the muscles, bands, and nerves. Most stunning I found the capillary system that leaves behind the shape of the body after plastination (see picture to the left, more here).